Modders and Poachers

Solo show organized by Mutter at Pakt, Amsterdam.

A modder is someone who makes changes to computer or games software or hardware (= equipment), or to vehicles, in order to create their own version, as a hobby.

The gaming modder scene first became popular in the early nineties with the release of the video game Wolfenstein 3-D (one of the first first-person shooters) by id-software. Demanding more active modes of spectatorship gamers began to modify the source code of the game. Sometimes on a cosmetic level such as changing the character model skins; sometimes by adding home made models of fantasy creatures or characters from other pop cultural universes and sometimes altering the core mechanics and gameplay of the game.

In his book Textual Poachers Henry Jenkins uses the term poachers to describe how a particular group of fans go through texts like favourite television shows and engage with the parts that they are interested in, unlike audiences who watch the show more passively. Specifically, fans use what they've "poached" to become producers themselves, creating new cultural materials in a variety of analytical and creative formats from "meta" essays to fanfiction, fanart, and more. He states: "Fan fiction is a way of the culture repairing the damage done in a system where contemporary myths are owned by corporations instead of owned by the folk."

Within the world of video games this poaching as Henry Jenkins describes it takes different forms like hard- and software modding, case modding, machinema and homebrewing.

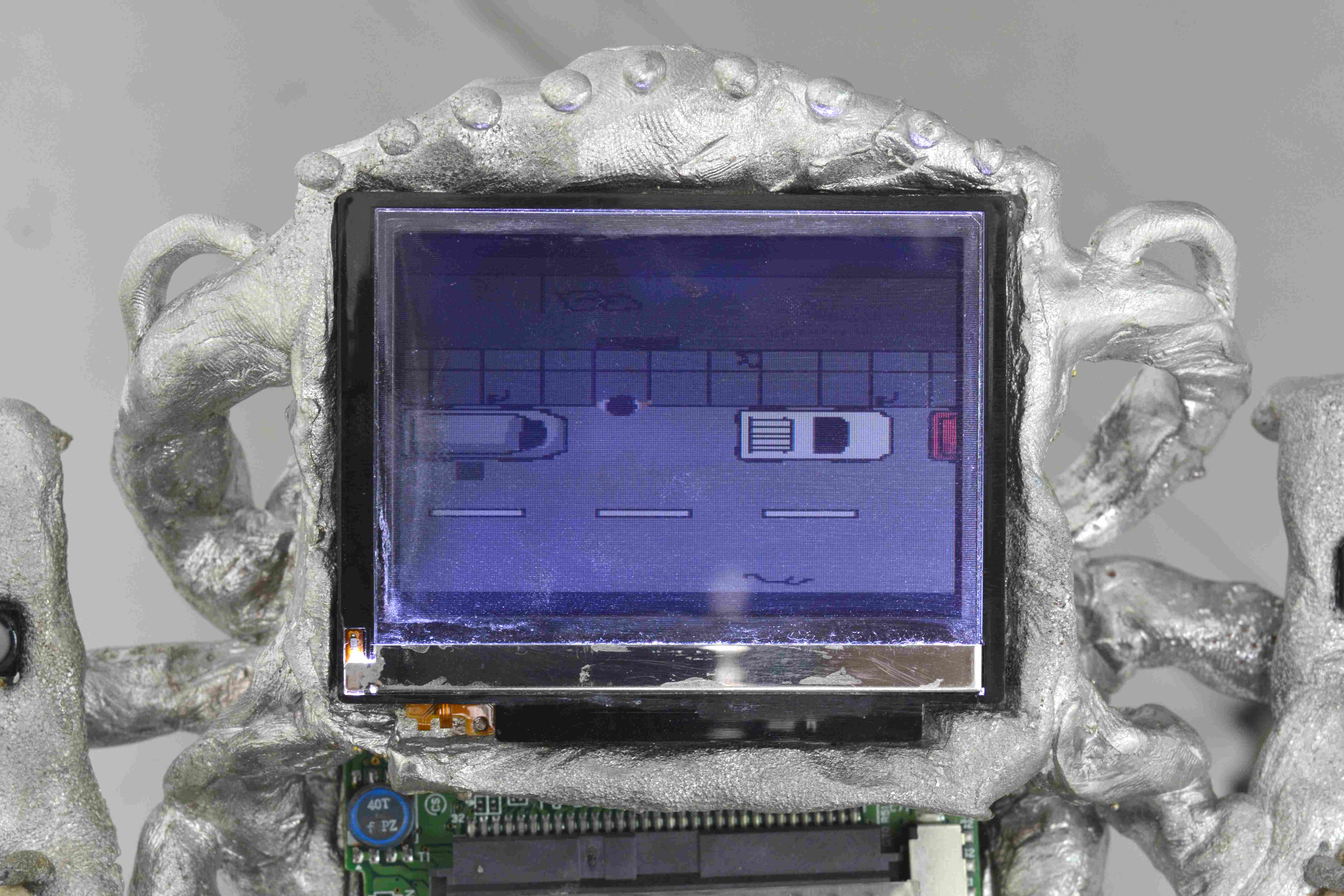

The homebrewing scene within gaming has seen a growth over the last decade and specifically the last few years. Small independent developers and hobbyist started to make and release video games for proprietary hardware platforms (old systems like the Nintendo Gameboy and Sega Dreamcast being popular choices) that were deemed or made obsolete by the gaming industry.

I find this homebrewing scene interesting because ever since the late 80’s the gaming industries’ main strategy for luring consumers to buy new products has been the promise of improved graphical processing power which in turn leads to more realistic renderings of video game characters and environments. The most striking example of this is the ‘’bit wars era’’ that ensued after the release of the TurboGrafx-16 video game console by NEC at the end of the 1980s.

In ‘Enter the bit wars’ Carl Therrien and Martin Picard describe: “James Newman has demonstrated the significant role of the discourse produced by the industry and the dedicated video game press in shaping the contemporary culture of material obsolescence. The introduction of the TurboGrafx-16 at the end of the 1980s partakes in a discursive framing of technology whose impact can still be felt in the way we construct history today: It helped solidify the widespread adoption of the biological metaphor (console “generations”), and of the technological warfare rhetoric.”

In rapid succession video game consoles with more and more bit (bits referring to the number of processor units used in the console) were released. (A small selection: Nintendo Entertainment system (1983) – 8 bit; TurboGrafx-16 (1987) – 16 bit; Sega Mega Drive 32X (1994) – 32 bit; Nintendo 64 (1996) – 64 bit). The word ‘bit’ became a synonym for power and the promise of more bits became a, often false, promise of a better gaming experience.

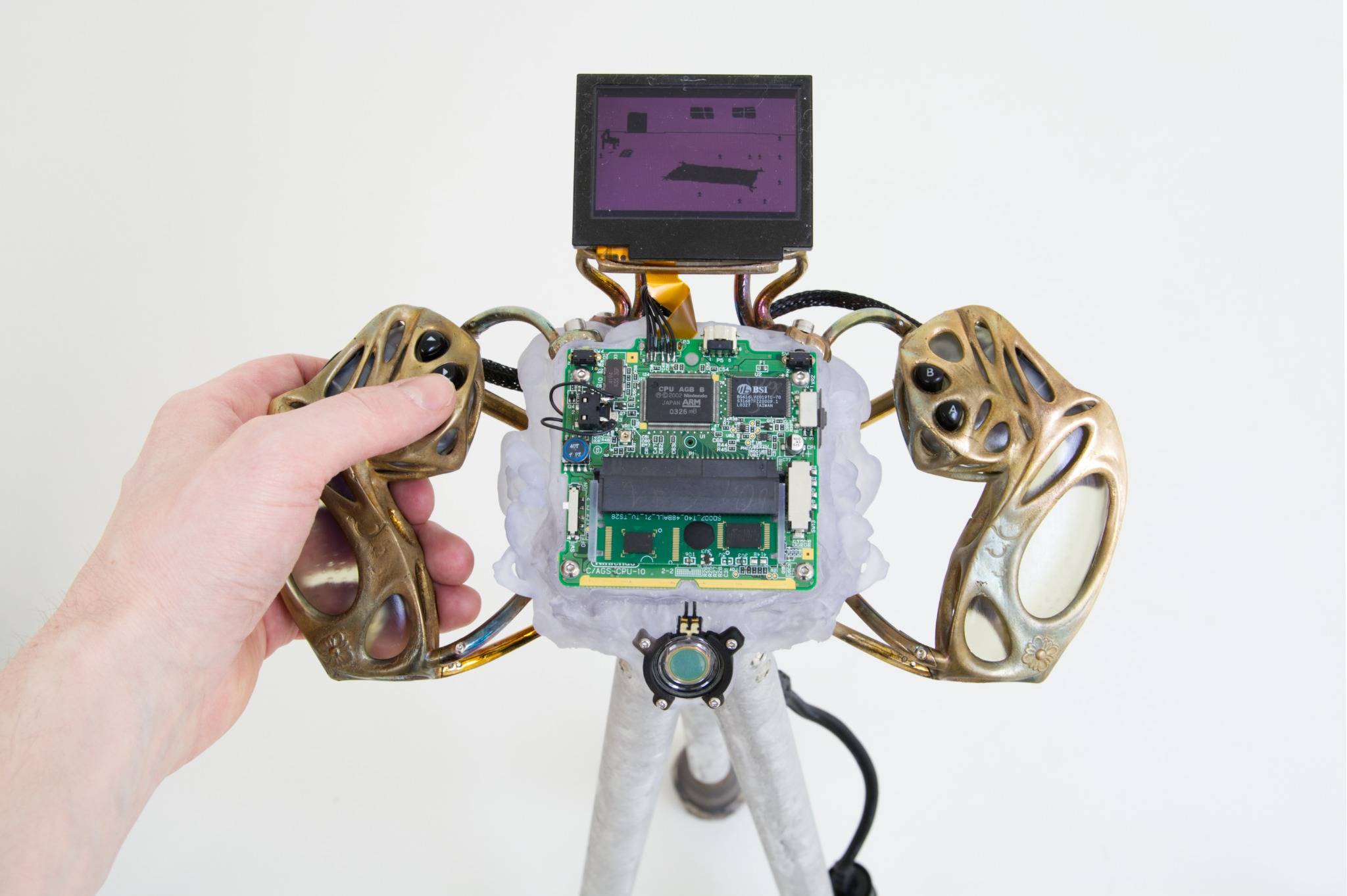

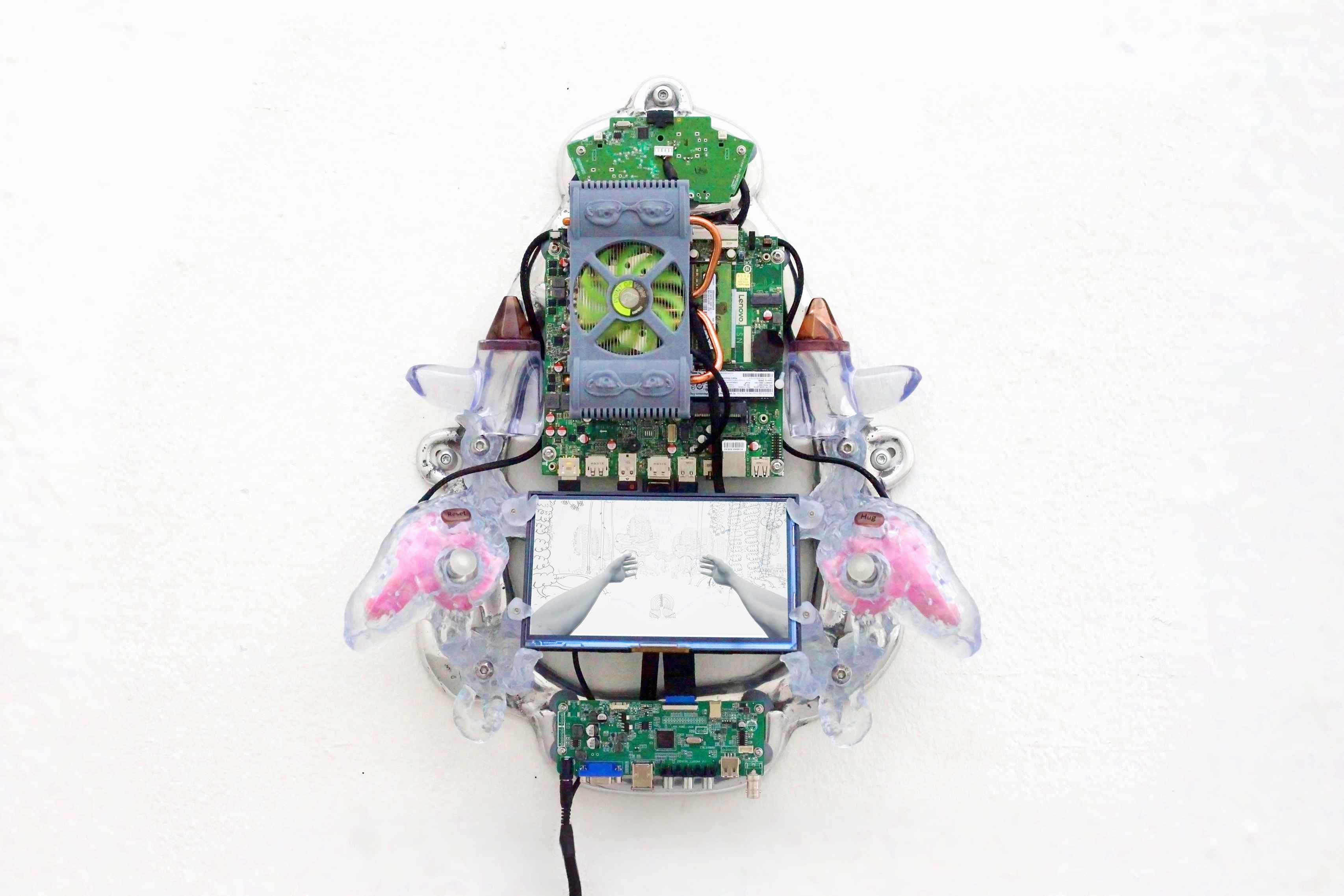

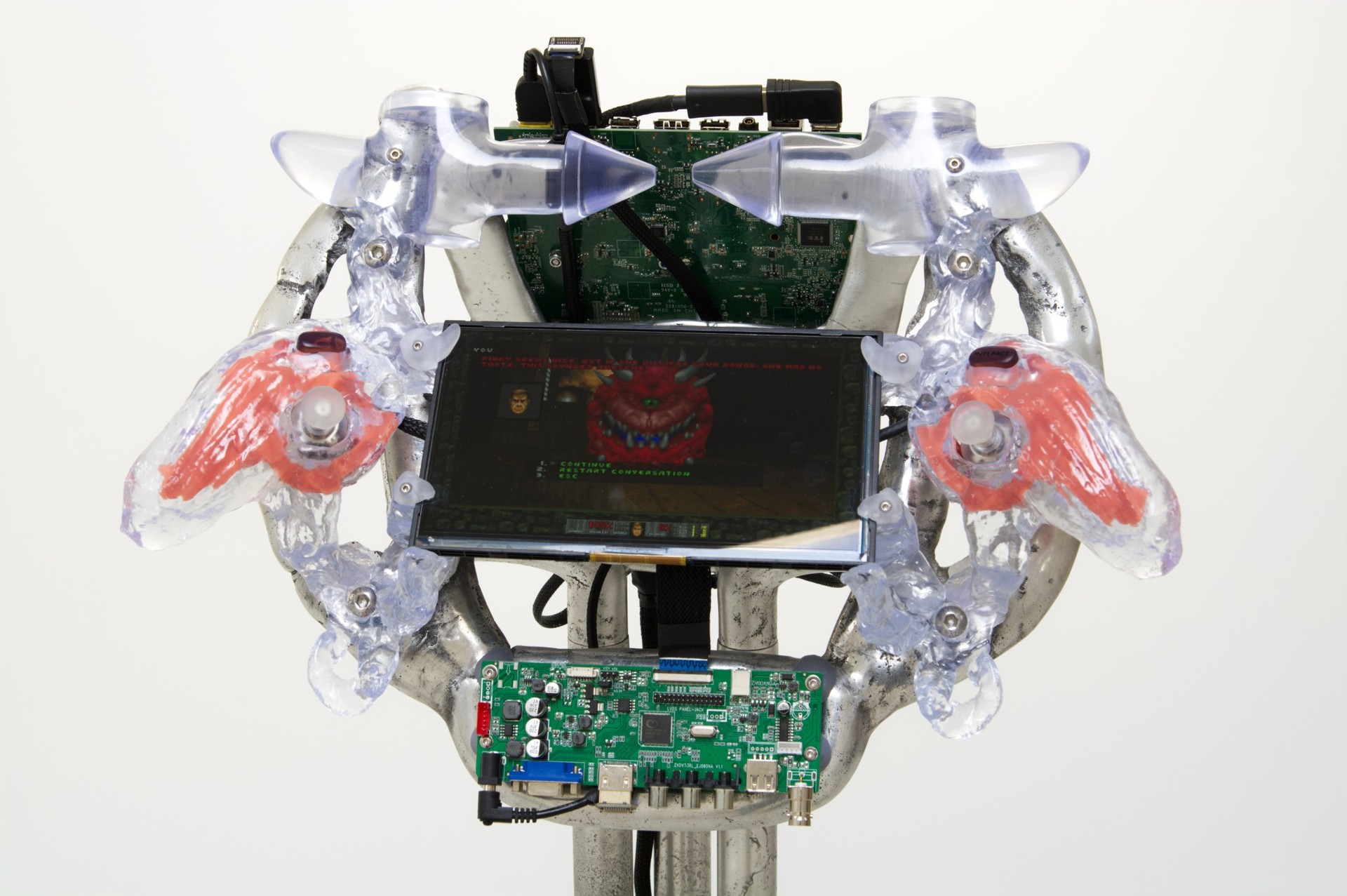

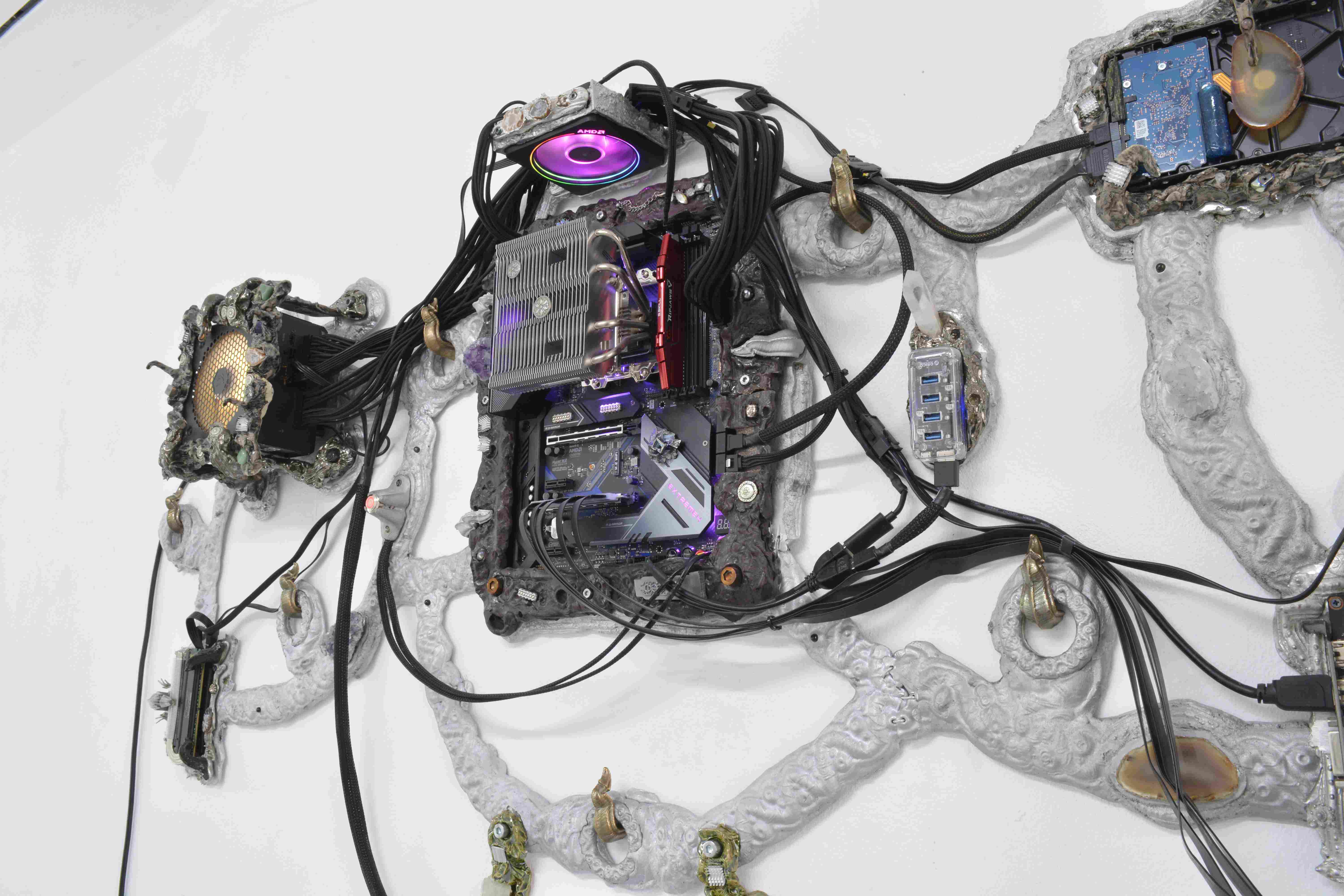

This constant push of the gaming industry for promoting ‘’better’’ and ‘’faster’’ hardware can very clearly be seen inside of the computer case of a contemporary gamer. It shows a techno-fetish wet dream, a technical utopia of laser cut heatsinks, water-cooling loops, anodized aluminium shells and individual addressable RGB lighting systems.

Within the homebrew community however the strive for next gen graphics is rendered obsolete. By making new games for older systems they express a counter establishment attitude that choses to use what we already have rather than to buy what we are told we need. It describes a technological recycling trend and at the same time gives them agency over the subjects and issues that they would like to see addressed in video games opposing the dominant industry offers of mostly violent and addictive games.

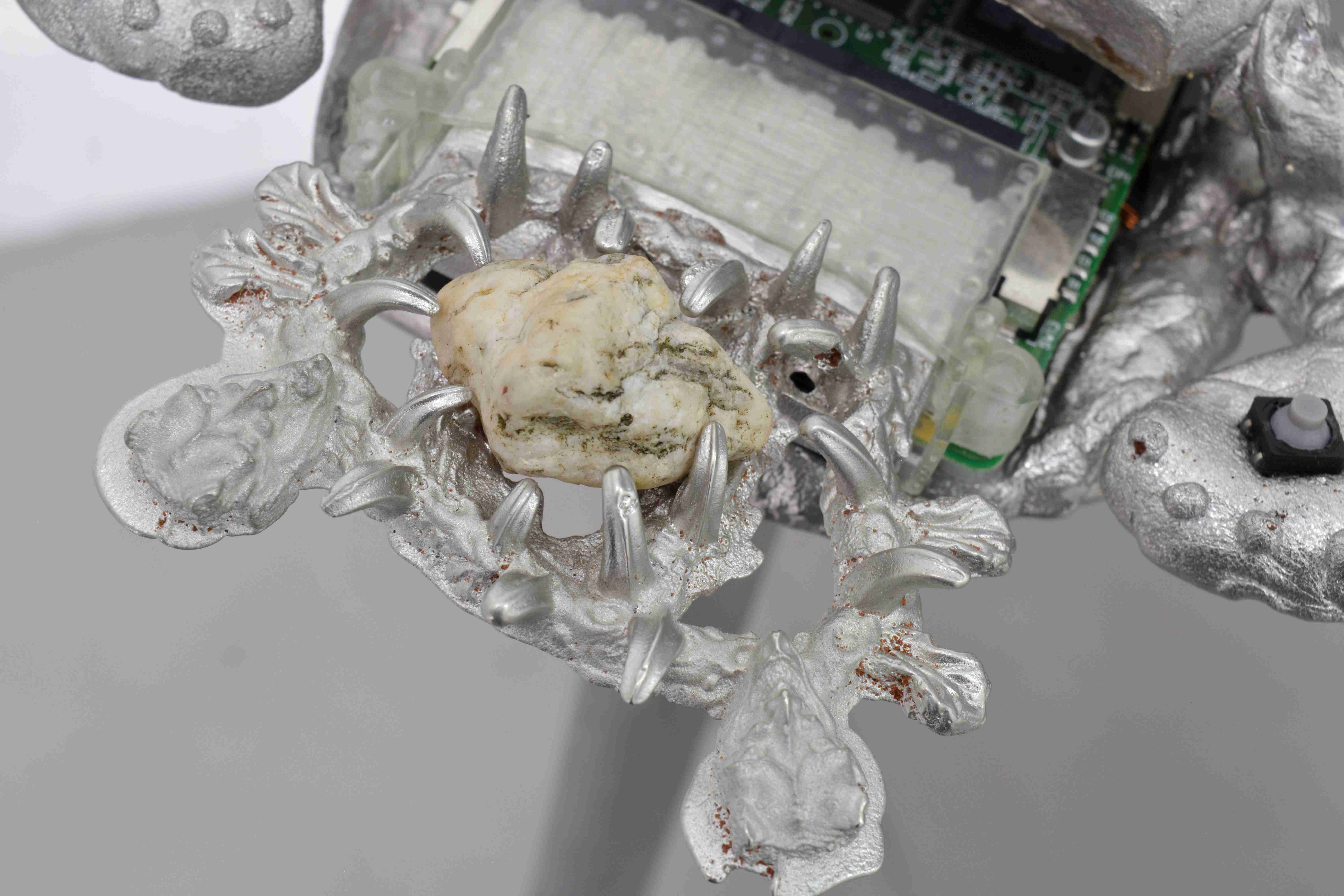

The worlds in video games are full of spiritual and decorative elements such as power crystals, life mana, magic, jewels and gems, ancient shrines and so on. But the computer of a gamer looks cold and standardised and only seems to want to convey notions of speed and power.

In his text ‘Geek Chick; Machine aesthetics, digital gaming, and the cultural politics of the case mod’ Bart Simon describes case modding (the act of modifying your computer by making it faster or more aesthetically pleasing) as following: “Yet despite the development of case modding as a form of folk art, it remains intimately tied to machine performance. For this reason, the most apt subcultural comparisons are probably hot-rod car culture and perhaps high-fidelity audio culture. Both of these, also very masculinist, subcultures value the visual aesthetics of machines combined with demonstrations of functional performance.”

Ever since the popularisation of the case mod during the rise of LAN-parties in the 1990’s (which were large events were gamers would come together with their pc’s to play video games on a local network) the gaming industry has incorporated this aesthetic into the computer hardware that they sell.

In my opinion there is no need for such a visual discrepancy to exists between the worlds in video games and the hardware that it is played on. A question that is pivotal in my practice is why technology can’t be associated with softer forms of expression, and how the world of computer hardware and technology can incorporate different visual message in their hardware. By researching how to merge the aesthetic values, fictions and properties of videogames and hardware I experiment with blurring the lines that divide what is software and what is hardware.