But Can It Run Doom

Solo show at Super Dakota gallery in Brussels

But Can It Run Doom is Janne Schimmel’s first solo show at the gallery. The show delves into the intersections of digital culture, the material conditions of gaming hardware, and the evolving role of technology in our lives. By reactivating older technologies, examining the design of our digital tools, and exploring new possibilities for digital expression, the exhibition challenges conventional narratives around intimacy, creativity, and resilience in a technology-driven world.

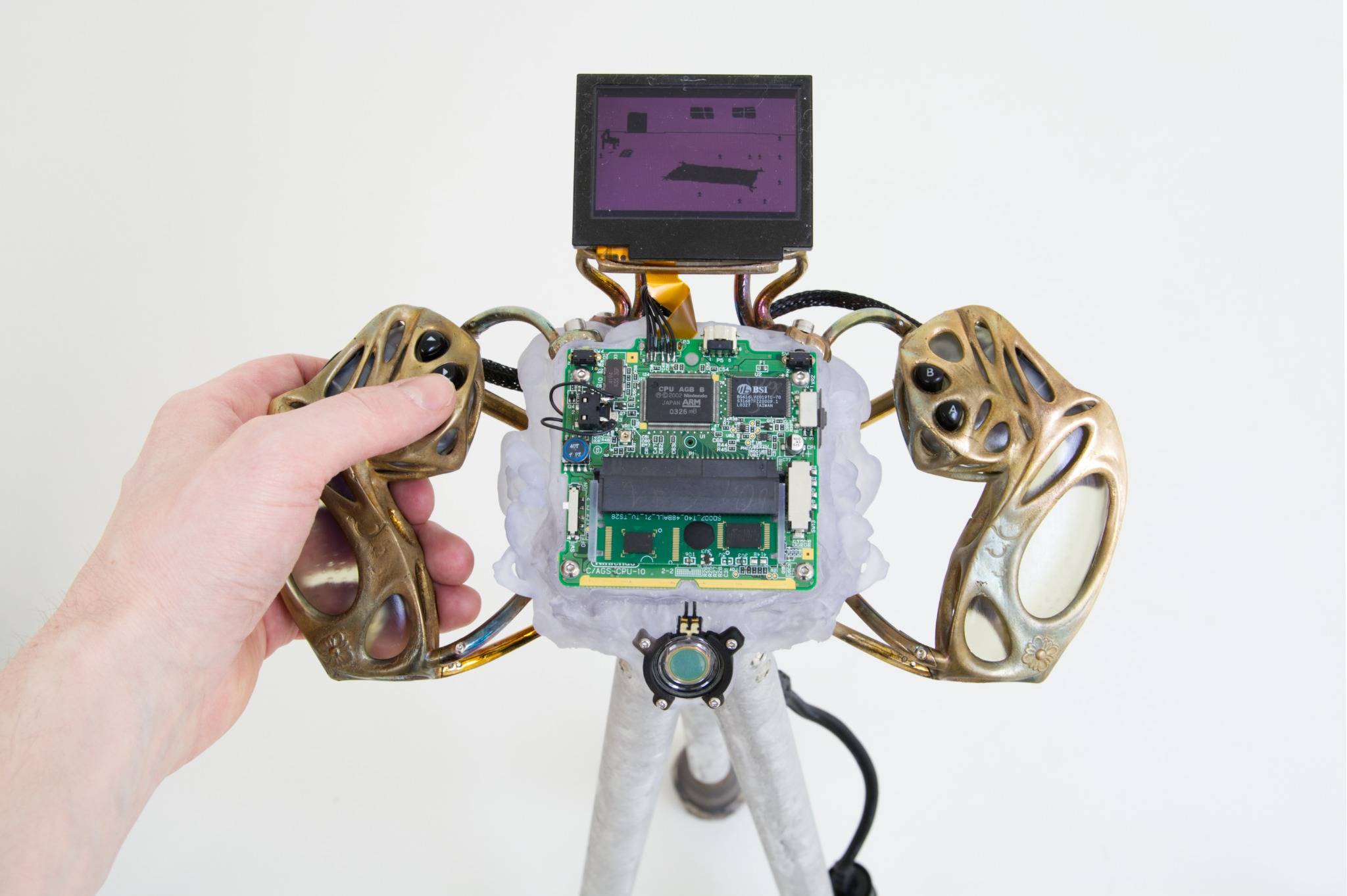

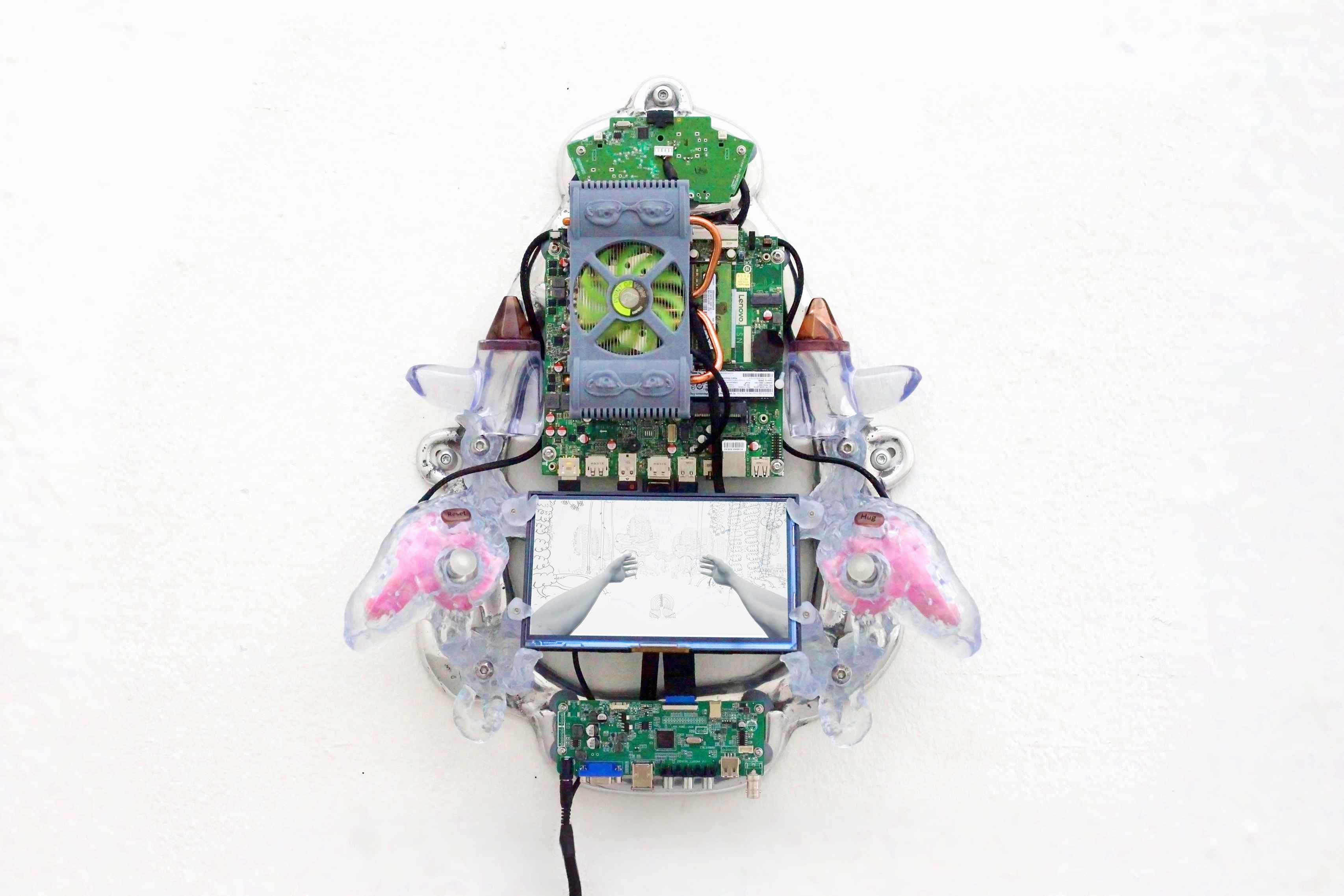

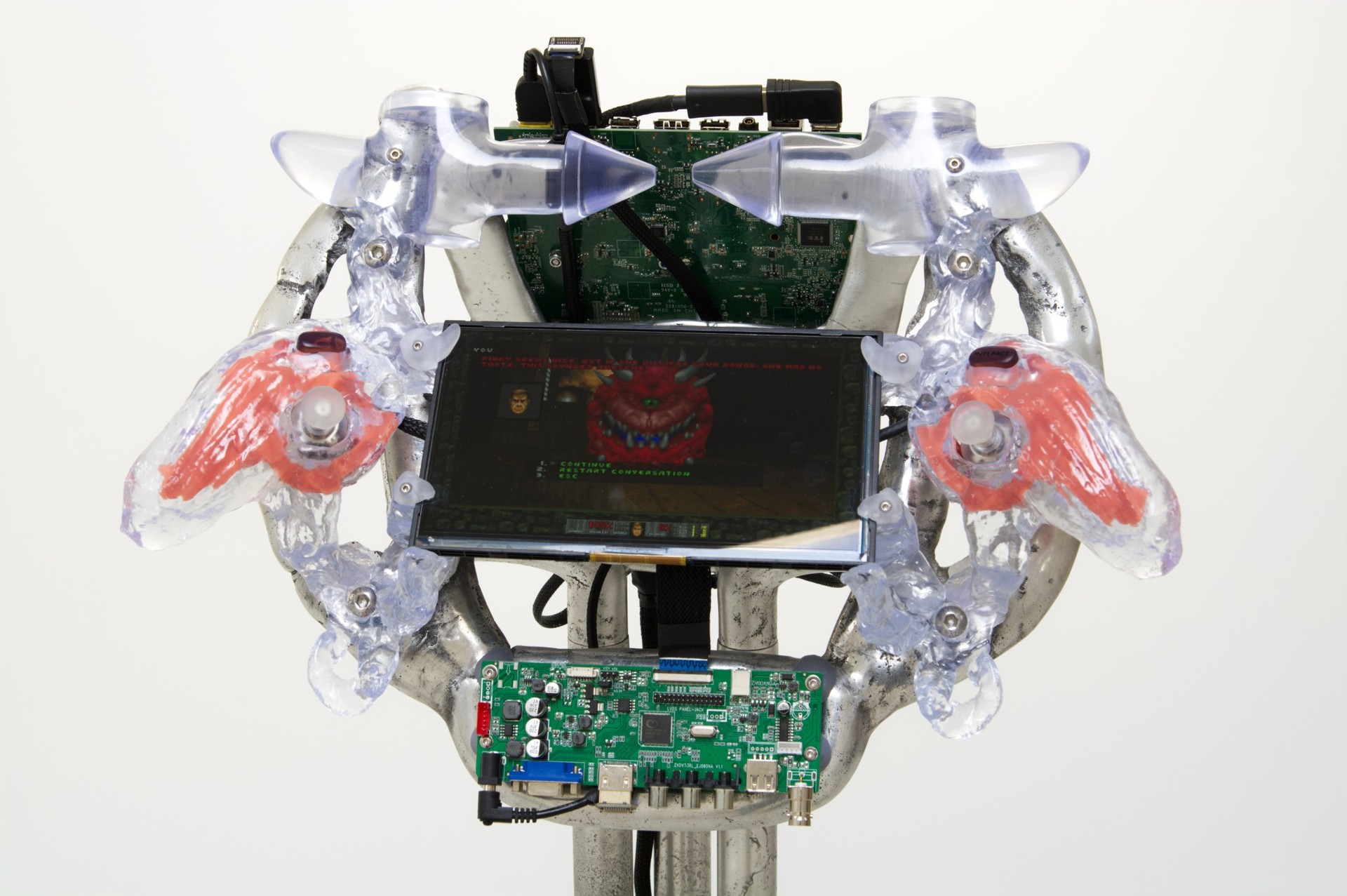

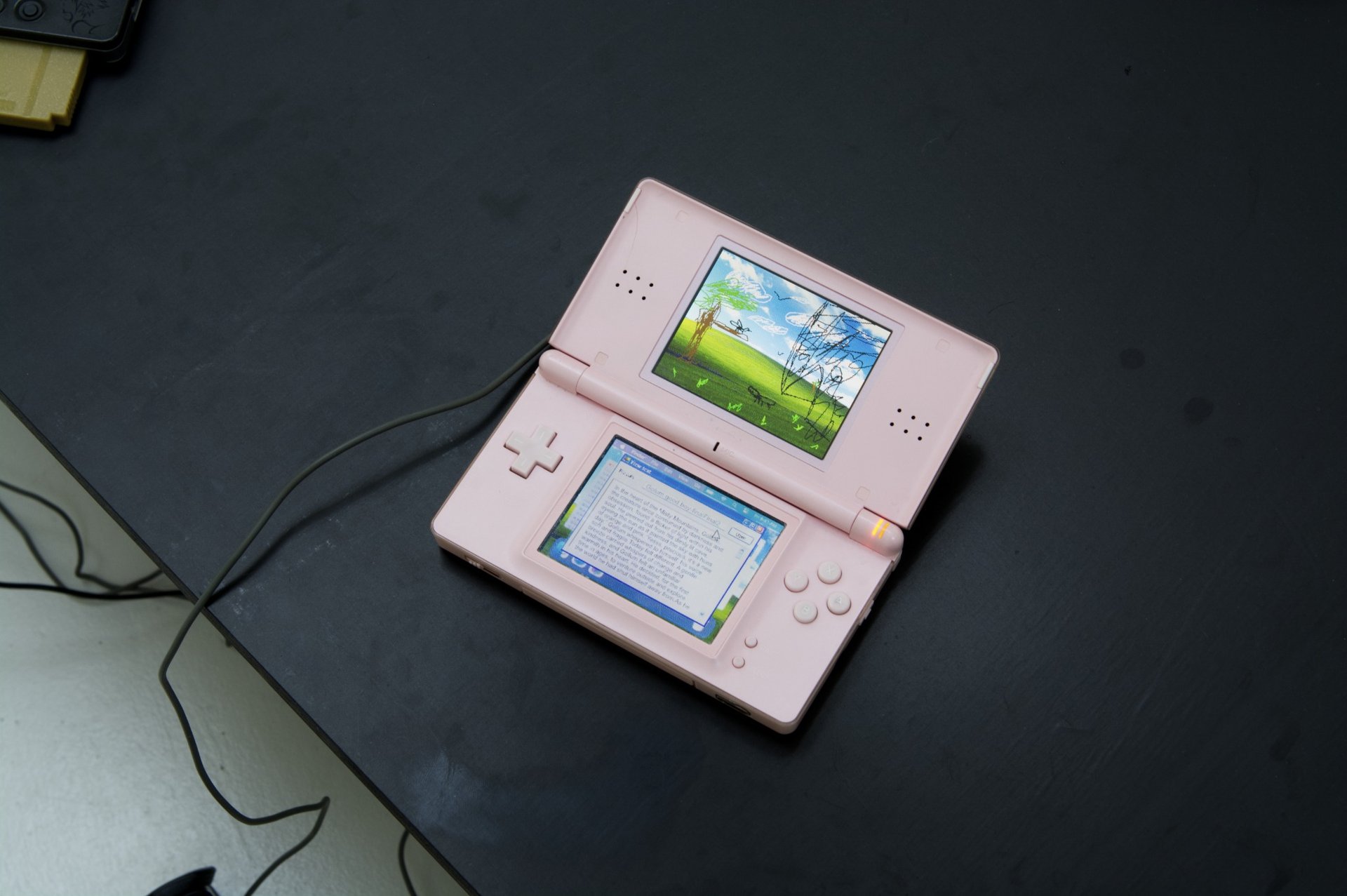

In But Can It Run Doom Schimmel reflects on the intersection of physical devices and digital spaces, critiquing the lack of emotional resonance in the design and marketing of computer hardware, particularly gaming devices, which prioritize speed, efficiency, and power over softer tactile attributes. Several works in the exhibition underscore the potential of empathy as an interactive mechanic. While many big budget games offer intricate combat systems and open-world structures they offer little room for kindness. With his works Doom Passive Mod and First Person Hugger that run on the sculptures Between Modder and Mud and Wall Flower Schimmel envisions alternative genres where players hug, listen, or converse with digital characters. This approach not only highlights the emotional range that has been overlooked in much of the commercial gaming culture, but also points to the deeper questions of how software design can mirror broader societal values. If the logic of a game dictates that picking up flowers can only result in violence, as reflected in Schimmel's experience from his youth when playing GTA: San Andreas—where his mother suggested he give a woman flowers, but the game only allowed him to hit her with them—Schimmel questions what this implies about our collective notions of “freedom” in virtual worlds.

In his series Strange Loop and Projections, Schimmel examines the process of transferring emotions between the physical and digital realms, focusing on motion capture technology and the intermediate phases of digitizing human expressions. Strange Loop highlights these “in-between” moments, showcasing how emotions are transformed during their digital re-creation.

The exhibition’s title But Can It Run Doom references a popular tech community challenge inspired by the 1993 first-person shooter game Doom. Developed by id Software, its developers made the game’s source code and level editor tools accessible, inviting players to create their own levels, textures, and modifications. This openness led to an explosion of user-created content and established Doom as a model for community-driven game development. The phrase gained popularity in 2006 when Doom was ported to the widely used Texas Instruments TI-83 educational calculator—porting refers to adapting software, such as a game, to run on a different hardware platform or operating system than it was originally designed for. This sparked a challenge to run the game on as many devices as possible, noteworthy examples include microwaves, ATMs, and even pregnancy tests. In 2022, hacker Sick Codes ported Doom to a John Deere tractor, highlighting the restrictive practices of manufacturers like John Deere, which use software locks to limit user repairs. This demonstration revealed the broader need for user agency and accessible repair options. The exhibition draws parallels between such cases and Schimmel’s work, which explores exposing hidden components of devices and modding older consoles like the Gameboy Advance and Nintendo DS to run custom games, echoing themes of accessibility and creative freedom.

User-generated games and modifications offer a lens through which to examine gaming as a participatory and emancipatory culture. Despite the commercial video gaming industry’s pressures to render older consoles obsolete, devoted communities continue to create and refine new content for systems released over three decades ago. Operating within a landscape where contemporary myths are often controlled by corporations, these “home-brew” networks reclaim agency by building their own narratives and questioning notions of authorship through open-source sharing. This ethos resonates with other communities—such as 3D printing and freeware circles—and informs how Schimmel sources virtual material and knowledge, fostering a culture of collective reinvention, and in turn, why he uploads his own work back to the internet to be used by others.

Recognizing that his work builds on a long tradition of homebrew game development, Schimmel is organizing a special program during the exhibition, which runs from January 25, 2025, to February 7, 2025. During this period, he invites various artists to present their games on the interactive sculptures displayed throughout the show (which normally run his own games). He has chosen artists from both the established art world and homebrew communities—creators who, in his view, are pushing the boundaries of game design in terms of both mechanics and naratives (see instagram post).

Credits:

Dr. Abbey made in collaboration with:

Stephan van der Woerd

Jonas Westendorp

Bart Hassink

Rein van der Woerd

Special thanks to:

Filippo Zimmermann

Helena Parys

Freeware used:

GB Studio

DS Game Maker

Tiled

Blender

LAN Messenger

Ultimate Doom Builder

Digital assets used:

Demon Screamer

'Demon Screamer' 3D model by 3DCULT

Livingroom Vol. 1 3D model by Unimodels

Movement sequence by Adobe Mixamo

First Person Hugger

Arms by lucasfalcao

Doom Passive Mod

Modification of Doom originally released by id Software

Strange Loop

RAW Expression Scans by 3D Scan Store

Projections 2

Character models and movement sequence by Adobe Mixamo

Game roms and animations can be downloaded on:

https://jannesch.itch.io/

3D models can be downloaded on:

https://www.thingiverse.com/jannesch/designs